Un-Happy Meals: Toy giveaways with restaurant children’s meals

Eating out used to be a special treat, but these days families are increasingly eating meals from restaurants. 25% of children’s calories come from fast-food and other restaurants.1 This trend is of public health concern because consumption of restaurant food is associated with increased caloric intake and poorer diets.2

The vast majority of kids’ meals include calorie-dense, nutritionally poor foods.

86% of children’s meals at the nation’s largest chain restaurants are high in calories; many also are high in sodium (66%) and saturated fat (55%).3

86% of children’s meals at the nation’s largest chain restaurants are high in calories; many also are high in sodium (66%) and saturated fat (55%).3

- Despite the health risks associated with sugar drink consumption, the majority of top restaurant chains feature sugar drinks with kids’ meals.

- French fries are the most common kids’ meal side option, and over three-quarters of the top restaurant chains promote sugar drinks through kids’ menus.4

Food marketing undermines children’s diets and health

Food and beverage marketing, including toy giveaways, influences children’s food preferences, food choices, diets, and health.5 Companies use marketing to shape children’s food preferences and choices, including by shaping what kids think of as food. Studies show that repeated exposure to fast food and soda, through advertising, marketing, and consumption, cultivates a pattern for future consumption and a preference for those and similar foods.6 Preschool-aged children recognize and prefer fast food and soda brands that are extensively marketed to them.6

Children under the age of 8 are unable to comprehend that the intent of advertising is to persuade them.5,7 The practice of enticing children to desire unhealthy meals using the prospect of getting a toy manipulates children’s inherent trust and lack of developmental maturity.

Children under the age of 8 are unable to comprehend that the intent of advertising is to persuade them.5,7 The practice of enticing children to desire unhealthy meals using the prospect of getting a toy manipulates children’s inherent trust and lack of developmental maturity.

Fast-food companies target children and adolescents with $714 million worth of marketing each year, promoting products, brands, and toy premiums to kids as young as 2 years old.8

- Toy giveaways make up almost half ($340 million) of that money, a marketing expenditure second only to TV advertising.8

- Fast-food restaurants sell more than one billion children’s meals with toys each year.8

Support parents, protect kids

Restaurants undermine parents’ ability to feed their children healthfully when they directly market unhealthy food choices to children. Restaurants should work with parents, not against them.

Restaurants undermine parents’ ability to feed their children healthfully when they directly market unhealthy food choices to children. Restaurants should work with parents, not against them.

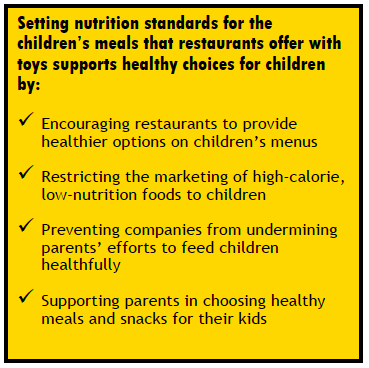

Restaurants have made some progress improving children’s meals, but progress has been modest and slow. Between 2008 and 2012, the percentage of restaurant children’s meals meeting nutrition standards increased from 1% to just 3%.3 Thus, states and localities need to nudge restaurants to do better. Disassociating toys and other rewards from unhealthy foods and improving the nutritional quality of restaurant children’s meals is a shared responsibility that should involve states, localities, restaurants, and parents.

Given the sky-high rates of childhood obesity, states and localities can support parents in helping children make healthy food choices by implementing nutrition standards for children’s meals that can be sold with toys. A recent study found that children were twice as likely to choose a healthier kids’ meal when healthier meals are served with toys.9

Given the sky-high rates of childhood obesity, states and localities can support parents in helping children make healthy food choices by implementing nutrition standards for children’s meals that can be sold with toys. A recent study found that children were twice as likely to choose a healthier kids’ meal when healthier meals are served with toys.9

Municipalities generally have the authority to regulate commercial products and practices to protect the public’s health, safety, and general welfare. Addressing restaurant children’s meals is a basic exercise of this authority. Parents have the right to guide their children’s food choices without so much interference from big food corporations.

For more information, contact the Center for Science in the Public Interest: nutritionpolicy@cspinet.org.

References

1. Lin B and Morrison RM (2012). Food and Nutrient Intake Data: Taking a Look at the Nutritional Quality of Foods Eaten at Home and Away From Home. Amber Waves, vol. 10, pp. 1-2.

2. Powell LM and Nguyen BT (2013). Fast-food and Full-service Restaurant Consumption Among Children and Adolescents: Effect on Energy, Beverage, and Nutrient Intake. JAMA Pediatr, vol. 167, pp. 14-20.

3. Batada A and Wootan MG. Kids’ Meals II: Obesity on the Menu. Washington, D.C.: CSPI, 2013.

4. Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity. Fast Food F.A.C.T.S. New Haven, CT: Rudd Center, 2013.

5. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or Opportunity? Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2006.

6. Cornwell T, McAlister A (2011). Alternative Thinking about Starting Points of Obesity. Development of Child Taste Preferences. Appetite, vol. 56, pp. 428-439.

7. Kunkel D et al. Psychological Issues in the Increasing Commercialization of Childhood: Report of the APA Task Force on Advertising and Children. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2004.

8. Federal Trade Commission [FTC] (2012). A Review of Food Marketing to Children and Adolescents. Follow Up Report. http://www.ftc.gov/os/2012/12/121221foodmarketingreport.pdf

9. Hobin, Erin P., David G. Hammon, Samantha Daniel, Rhona M Hanning, and Steve R. Manske. The Happy Meal Effect: The Impact of Toy Premiums on Healthy Eating Among Children in Ontario, Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, vol. 103, pp. 244-248.